Clearer Understanding of 95% Confidence Interval Through The Lens of Simulation

By Ken Koon Wong in r R confidence interval simulation my own notes

January 15, 2024

I’m now more confident in my understanding of the 95% confidence interval, but less certain about confidence intervals in general, knowing that we can’t be sure if our current interval includes the true population parameter. On a brighter note, if we have the correct confidence interval, it could still encompass the true parameter even when it’s not statistically significant. I find that quite refreshing

I always thought I knew what a confidence interval was until I revisited the topic. There are plenty of great resources out there covering the same material. However, nothing beats learning through trial and error with your own code and simulations. This may be a repetition of materials available on the web.

Objectives:

- What Is Confidence Interval?

- What Does It Actually Mean?

- Let The Simulation Begin

- Final Thoughts/Lessons Learnt

What Is Confidence Interval?

Per Wikipedia:

Informally, in frequentist statistics, a confidence interval (CI) is an interval which is expected to typically contain the parameter being estimated. More specifically, given a confidence level gamma (95% and 99% are typical values), a CI is a random interval which contains the parameter being estimated gamma % of the time. The confidence level, degree of confidence or confidence coefficient represents the long-run proportion of CIs (at the given confidence level) that theoretically contain the true value of the parameter.

What Does It Actually Mean?

When conducting an experiment, calculating a 95% confidence interval for the treatment effect doesn’t mean there’s a 95% chance that this specific interval contains the true effect. Instead, it means that if you were to repeat the experiment many times, approximately 95% of those confidence intervals would contain the true effect. The 95% confidence level indicates how often the method will produce intervals that capture the true parameter rather than the probability that any single interval captures it. This understanding is essential to accurately interpret a single confidence interval in your study.

It’s important to understand that there is no way to know whether your current confidence interval is part of the 95% that covers the true effect. This can be frustrating, but it’s a limitation of the method.

It is more intuitive to assume that the current confidence interval is one of those 95% that contain the true estimate and interpret it that way. Additionally, the 95% confidence interval coverage does not need to be “significant” to cover the true parameter; it inherently contains if the interval so happens to be one of those 95%.

If you’re still confused, don’t worry! Running simulations and visualizations can provide a clearer explanation. It’s worth noting that confidence intervals are estimated using different techniques, some more accurate than others, but we won’t be covering that here today.

Let The Simulation Begin

What If We Know The Truth Of The Population?

library(tidyverse)

library(kableExtra)

library(pwr)

# population parameters

n_pop <- 10^6

placebo_effect <- 0.2

treat_effect <- 0.5

true_y <- treat_effect - placebo_effect

# simulation

set.seed(1)

placebo_pop <- rbinom(n_pop, 1, placebo_effect)

treat_pop <- rbinom(n_pop, 1, treat_effect)

# population dataset

df_pop <- tibble(outcome_placebo=placebo_pop, outcome_treat=treat_pop) |>

mutate(id = row_number())

Let’s set up a world where we know everything! Say, we know for sure whether a treatment works for certain people and won’t for others. Same for placebo. And also sometimes, both treatment and placebo work for certain people or nothing works. With this method, we constructed a world where we know the truth and simulation comes using sampling of this population.

The above code sets up such environment. Let’s run through what they mean.

n_popis the total population, in whom the condition we are interested in.placebo_effectis set at 20%, meaning there is a probabiliy of successful outcome for 20% of the population if we were to use placebo. This could be that condition just takes time to cure itself, or that there is actual placebo effect.treatment_effectis set at 50%, whereby 50% of population will achieve successful outcome when given the treatment.- We then use

rbinomto simulate both effects for ALL population of interest and save it into dataframe calleddf_pop.

Here the placebo and treatment effects are made up. You can simple change the numbers to create another world. Here you can practice large, moderate, small or no effect.

Let’s take a look what df_pop looks like

df_pop |>

head(10) |>

select(id, outcome_placebo, outcome_treat) |>

kable()

| id | outcome_placebo | outcome_treat |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 1 |

| 9 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 | 1 |

id is unique individual. outcome_placebo is the outcome when placebo is given. outcome_treat is outcome when treatment is given. 0 means not successful. 1 means successful. Notice how we have outcome for both placebo and treatment for each individual. Look at id 6 where outcome is successful regardless of treatment and placebo.

There you have it! Your own made up world of finite population where you know what works, what doesn’t. The beauty of this is that we can then sample from this known world where we know exactly what the treatment effect is (not an estimate), a fixed parameter. Hence, there is no reason to calculate confidence interval because it does not make sense to have one.

Let’s Simulate Multiple RCT

n_cal <- pwr.2p.test(h = ES.h(treat_effect,placebo_effect), power = 0.8, sig.level = 0.05)$n |> ceiling()

Assuming we want 80% power and alpha of 5%, and effect of 0.6435011 we need 38 per group.

df_full <- tibble(iter=numeric(),sample=numeric(),mean=numeric(),lower=numeric(),upper=numeric(),pval=numeric())

for (j in 1:12) {

df <- tibble(iter=numeric(),sample=numeric(),mean=numeric(),lower=numeric(),upper=numeric(),pval=numeric())

# set.seed(1)

n <- n_cal*2

for (i in 1:100) {

df_sample <- df_pop |>

slice_sample(n = n) |>

rowwise() |>

mutate(random_treatment = sample(0:1,1),

outcome = case_when(

random_treatment == 1 ~ outcome_treat,

TRUE ~ outcome_placebo

))

treat <- df_sample |>

filter(random_treatment == 1) |>

pull(outcome)

placebo <- df_sample |>

filter(random_treatment == 0) |>

pull(outcome)

ci <- prop.test(x = c(sum(treat),sum(placebo)), n = c(length(treat),length(placebo)), correct = F)

mean <- mean(treat) - mean(placebo)

# lower <- mean - 1.96*sqrt(mean*(1-mean)/n) #wald, let's use wilson instead

lower <- ci$conf.int[1]

upper <- ci$conf.int[2]

pvalue <- ci$p.value

# upper <- mean + 1.96*sqrt(mean*(1-mean)/n) #wald, let's use wilson instead

df <- df |>

add_row(tibble(iter=j,sample=i,mean=mean,lower=lower,upper=upper,pval=pvalue))

}

df_full <- df_full |>

add_row(df)

}

Let’s break down the code above:

- Create an empty dataframe called

df_full - Run 2 for loops

- 1st for loop -> 12 sets (these are sets of trials)

- 2nd for loop -> 100 trials per set (each trial means one experiment)

- Set

nfor total of2times of calculated number needed for power of 80% and alpha of 5% - Sample

2xnof the population - Assign randomly placebo or treatment for each individual, then select outcome accordingly

- Use

prop.testfor test of equal or given proportions- extract average treatment effect

- extract confidence interval (uses Wilson’s score method)

- extract p-value (this is more to showcase meaning of power)

- Append dataframe

df_full |>

head(10) |>

kable()

| iter | sample | mean | lower | upper | pval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0.3473389 | 0.1492637 | 0.5454142 | 0.0018010 |

| 1 | 2 | 0.1448864 | -0.0569022 | 0.3466749 | 0.1746284 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.2464986 | 0.0436915 | 0.4493057 | 0.0243074 |

| 1 | 4 | 0.3492723 | 0.1482620 | 0.5502827 | 0.0016048 |

| 1 | 5 | 0.1842105 | -0.0229481 | 0.3913691 | 0.0874454 |

| 1 | 6 | 0.1843137 | -0.0384418 | 0.4070693 | 0.0913694 |

| 1 | 7 | 0.3756614 | 0.1632469 | 0.5880759 | 0.0004565 |

| 1 | 8 | 0.4816355 | 0.2976731 | 0.6655978 | 0.0000116 |

| 1 | 9 | 0.2437276 | 0.0518956 | 0.4355596 | 0.0104277 |

| 1 | 10 | 0.1777778 | -0.0259180 | 0.3814736 | 0.0959556 |

Let’s Visualize!

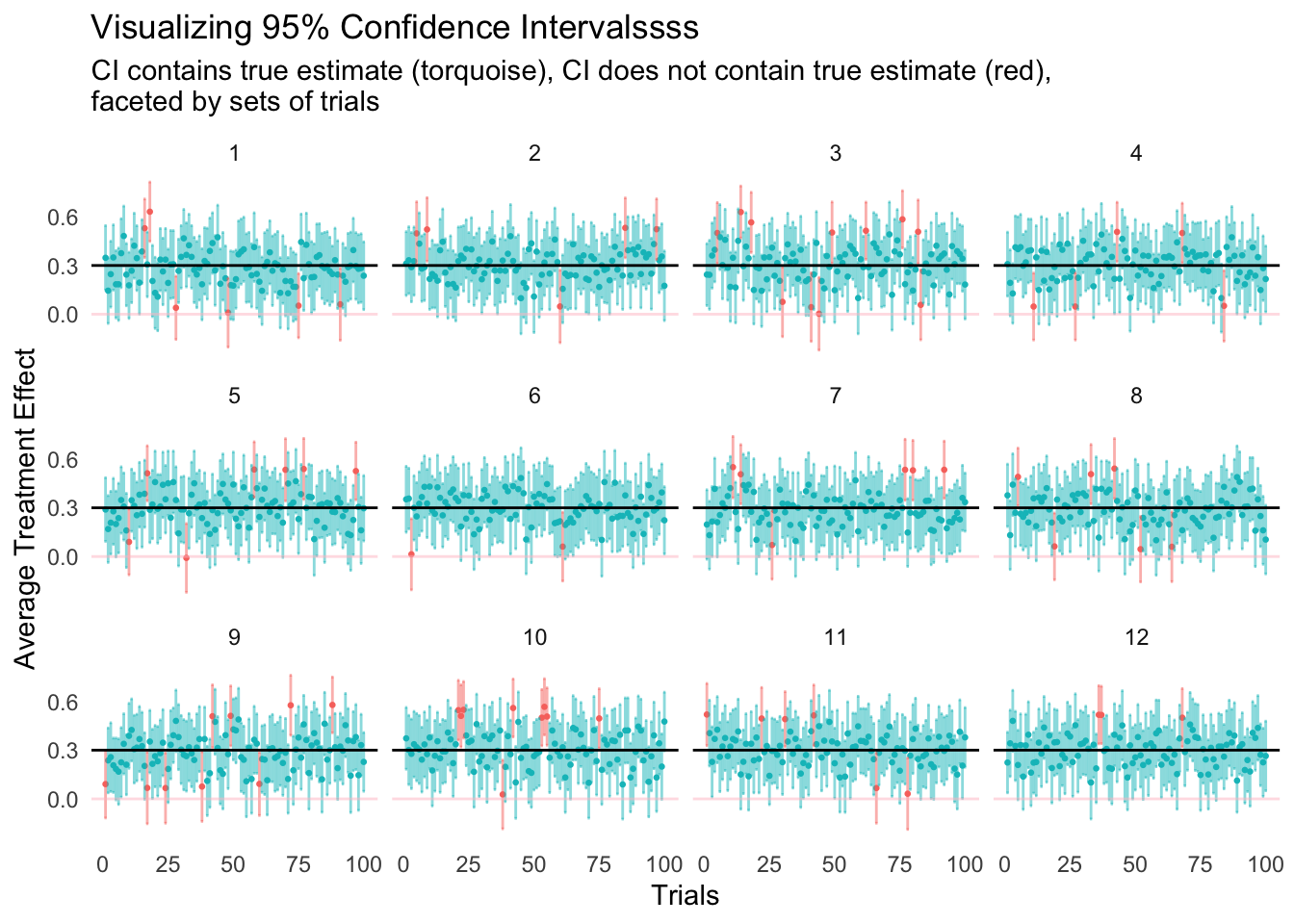

df_full |>

mutate(true_found = case_when(

lower < true_y & upper > true_y ~ 1,

TRUE ~ 0

)) |>

ggplot(aes(x=sample,y=mean,color=as.factor(true_found))) +

geom_point(size=0.5) +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=lower,ymax=upper), alpha=0.5) +

geom_hline(yintercept = true_y) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "pink", alpha = 0.5) +

# geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = -0.2, ymax = 0, xmin = 0, xmax = 101), fill = "pink", alpha = 0.3) +

ylab("Average Treatment Effect") +

xlab("Trials") +

ggtitle(label = "Visualizing 95% Confidence Intervalssss", subtitle = "CI contains true estimate (torquoise), CI does not contain true estimate (red), \nfaceted by sets of trials") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(panel.grid.major = element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

legend.position = "none") +

facet_wrap(.~iter)

Let’s see what is going on here:

- Create a new column

true_found- If the

lowerandupper, remember these are 95% CI, contain the true parameter (true_y) then throw a1, else0

- If the

- Create

ggplotx-axis: 1 to 100 trialsy-axis: Average Treatment Effecterrorbar: lower and upper 95% CI

- Color

torquoise: 95%CI contain true treatment effect - Color

red: 95%CI does not contain true treatment effect Horizontal blackline: True treatment effect of the populationHorizontal pinkline: Zero treatment effect, any trials with 95%CI crosses this will have p-value >= 0.05

This is quite fascinating! It is approximately true that ~95% (to be exact 93.75) of the confidence intervals contain the true parameter (treatment effect).

Also note that there are quite a few trials were not able to correctly reject the null hypothesis, 19.8333333% to be exact. Does that look familiar? It’s beta, isn’t it? If we flipped it around, the proportion of trials that correctly rejected the null hypothesis were 80.1666667%, which is essentially our power!

Final Thoughts/Lessons Learnt

- Guide to Effect Sizes and Confidence Intervals, Highly recommended! I think, is going to be a great resource in the fundamentals of effect size and confidence interval. I’ll keep my eye on this as it develops into a living document!

- Confidence Intervals for Discrete Data in Clinical Research is also a great book diving deep into estimating confidence intervals using different formulae.

- It dawned on me that we can never be certain whether our current confidence interval, whether significant or not, contains the true parameter. It is only useful if we assume, our current confidence interval, is one of the approximately 95% of intervals that do contain the true parameter.

- Correct me if I’m wrong, one of the more positive note of confidence interval, if we have the “right” one, whether it crosses zero or not (e.g. accept the null), may still contain one of the true parameter. I found this suprisingly positive!

df_full |>

mutate(true_found = case_when(

lower < true_y & upper > true_y ~ 1,

TRUE ~ 0

)) |>

filter(true_found == 1, pval >= 0.05)

Take a look at iter 1, sample 21. Even though the ATE estimate is off & failed to correctly reject the null hypotehsis, the CI still contains the true parameter (which is 0.3), which to me is quite fascinating!

Take a look at iter 1, sample 21. Even though the ATE estimate is off & failed to correctly reject the null hypotehsis, the CI still contains the true parameter (which is 0.3), which to me is quite fascinating!

- Finally, should we rename

confidence intervalto something else less confusing? Maybe it’s just me.

If you like this article:

- please feel free to send me a comment or visit my other blogs

- please feel free to follow me on twitter, GitHub or Mastodon

- if you would like collaborate please feel free to contact me

- Posted on:

- January 15, 2024

- Length:

- 9 minute read, 1772 words

- Categories:

- r R confidence interval simulation my own notes